WY Day 6 - Great Art, Gunslingers, and Gorgeous Scenery

Today I started with a short drive to Cody, one of the bigger cities in the state that I had only briefly passed through earlier in the week and wanted to spend more quality time with. It’s named after Buffalo Bill Cody, and the Buffalo Bill name is all over the town so I feel like they must really hate the Silence of the Lambs for forever making that weirder than it needs to be. My first stop was for some excellent coffee from Rawhide Coffee. They’ve got a homey western vibe, good strong brews, and a fun sense of humor as evidenced by this charming (and alarmingly accurate) sign out front.

Note the cool customer in the top left

My major stop for the day was the Buffalo Bill Center of the West, a Smithsonian Affiliate museum and one of the most recommended spots outside of Yellowstone in the state. You’ll definitely want to set aside a full day for this museum because while the front is pretty grand and beautifully constructed, it doesn’t quite reveal just how much bigger the museum is inside. To call it one museum is even a bit misleading, as it actually contains five distinct museums: The Buffalo Bill Museum, The Cody Firearms Museum, The Whitney Western Art Museum, The Draper Natural History Museum, and the Plains Indian Museum. So yeah, it’s big.

If I was slightly daunted about committing my day to one (mega)museum, I was immediately put to ease by these incredibly weird and funny membership signs. This was gonna be my kind of place.

One thing I was disappointed about with the sheer size of the Buffalo Bill Center was that I had initially hoped to include the Museum of the Mountain Man in my day, but it didn’t seem possible after all. Luckily in the lobby of the museum was a small case of artifacts from real life Mountain Men. My favorite thing I learned that was that the real life guy who the movie Jeremiah Johnson was based on, was actually a guy called Liver-Eating Johnson because he was known for eating the livers of his enemies after he killed them. For some crazy reason, there were no scenes of Robert Redford going full cannibal and I just can’t imagine why.

Of the five museums, I decided to start with the Whitney Museum of Western Art, because it was the one I was most excited about. I began with some 19th century Western art from the first painters and sculptors to venture out into the wild frontier. The people in these paintings might have had some slightly goofy anatomical proportions, but they were more than made up for by the radiant shimmering landscapes.

When it comes to landscapes though few could compete with Albert Bierstadt and Thomas Moran who created sweeping scenes that were such an amazing blend of documentary realism and fantastic romanticism:

The next gallery was uniquely Wyoming showcasing several decades worth of art depicting Yellowstone and all its unique and grandiose features. I liked that there was a combination of commercial work done for advertising and land surveys as well as pure artistic endeavors where the strange and beautiful landscapes captured the artists’ imaginations.

My favorite Yellowstone pieces included: some intensely expressionist globby landscapes by Theodore Waddell; a dramatic oil painting by Carl Preussl of Old Faithful doin’ its thing; and a shockingly realistic capturing of one of the prismatic hot springs by M.C. Poulsen (I think those were his actual initials, not his rap name).

The next gallery was all about Wildlife Art. You’d think I’d be bored of it after the similarly massive museum of Wildlife Art; but with artists like Carl Rungius, William Leigh; and James Audubon, it’s hard to not be consistently impressed by the diversity of western fauna and the equally diverse different artistic interpretations of it.

My favorite pieces were: the supremely bizarre grizzly bear picnic by Anne Coe and the graceful, powerful, and uncannily realistic moose sculpture by T.D. Kelsey that positively dominated the lobby space.

The next exhibit was a special showcase of the traditions of Western sculptures showing every step of the process from early drafts to plaster molds to finished bronzes. It was a neat peek behind the curtain, as well as also just a great display of works from greats like Frederic Remington and C.M. Russell.

Next up we had some 20th century works by the fantastic painters and illustrators who really created the visual language we associate with the Old West in popular culture. My favorite pieces included: a very Western Still life combining frontier artifacts and photos of legendary figures by Astley Cooper; a frantic C.M. Russell action set piece; a tender father and son teaching moment by Winnold Reis; a prairie Madonna by W.H.D. Koerner; some majestic Western Impressionism by Maynard Dixon; more incredibly dense storytelling by Russell; a beautiful neo-classical bronze relief of a Buffalo hunt by Charles Rumsey; and a simultaneously gorgeous and violent illustration by of hunters confronting a bear by N.C. Wyeth.

Next up was a real treat: a full scale recreation of the home studio of Frederic Remington complete with landscape sketches, hunting trophies, and collected artifacts from a life lived out on the open frontier. For a man who once wrote to his uncle that he didn’t want to anything with his life that required “extraordinary effort” he did pretty alright, casually shaping a whole generation of American painters to focus more on people than landscapes.

From the first time I saw Remington highlighted in a museum in Oklahoma, I really fell in love with his rich and simple storytelling. Like Russell, whom he inspired, he’s just able to cram so much life and energy into a small still image. I was really happy to see a bigger exhibition dedicated to just him, and It was pretty cool seeing the early impressionistic landscapes he eventually moved away from alongside the photorealistic cowboy and Native American scenes that made him famous.

And of course, there’s his insanely gravity defying bronze sculptures just to really show off what the guy was capable of:

Up next was more contemporary and modern western pieces. Here you see the blending of influences from the early Western painters combined with impressionist and surrealist European painters, photo-realists, Pop-art, and Abstract Expressionist influences that end up showing a century’s worth of art trends playing out over an Old West backdrop:

Of the more modernish paintings, my favorites were: the massive, hauntingly luminescent Flooded Cascade by Stephen Hannock; the operatically pop-arty Flight from Destiny by Bill Schenck; the unreasonably photo-realistic acrylic Prairie Rattler by Don Coen (it’s insane!); and the playful mixed media Western Man with Beer and Dog by Audrey Roll-Priessler that wonderfully blends the mundane and the surreal.

I was also really happy to see some highlighted works contemporary Native American artists, because as I’ve learned over countless museums, there’s an amazing body of work being produced everyday by these artists that is in real danger of being totally overlooked and ignored. It would have been particularly bad for a museum named in honor of a man who at one point made a living killing Indians to ignore their continued contributions to this country and the art world, but luckily as we’ll see more of later, the museum does a pretty good job dealing with Buffalo Bill’s complicated legacy with Native Americans while doing its best to right what wrongs it can. Of this section of the museum some highlights included: a hypnotically colored warrior portrait by Fritz Scholder; an incredibly dense painting by Allan Mardon (a non-Native artist, who studied extensively with Native peoples) done in the style Plains Indian ledger art that seeks to tell a more honest and complete account of the Battle of Greasy Grass (the Lakota name for the Battle of Little Bighorn) based on hundreds of interviews with Native historians; a moody impressionistic cattle drive rendered in stunning colors by Earl Biss; and variation on Henri Rousseau’s Sleeping gypsy by David Bradley that depicts Tonto asleep among some dirty magazines while the Lone Ranger inexplicably and hilariously hides in the bushes.

There were also a number of impressive sculptural works including: a dreamily precarious stack of fruits on the antlers of a moose by Brad Rude; a wild cubist glazed stoneware sculpture by Rudy Autio where its really hard to tell where the horse ends and the rider begins; an earthenware bust of the museum’s namesake by Peter Vandenberge; and an elegantly modern bronze and limestone Buffalo by Steve Kestrel.

Far and away the most impressive sculpture was one that maybe doesn’t quite catch your eye as immediately as the others. Bale Creek Allen’s bronze Tumbleweed is a mindblowing feat of craftsmanship and attention to detail whose magic really lies in how imperceptible all that work is. It looks very simply like a tumbleweed, but to cast something with so much negative space such small spindly parts in bronze required the artist spending hours and hours welding every little branch together. The more you stare at it and forget that it’s a sculpture the more incredible it becomes.

Walking down a hallway of all black and white pieces by masters like C.M. Russell and Will James, I unintentionally stumbled into the next of the five museums, but these pieces made the journey just as fascinating as the destination.

There also happened to be an entire one room cabin (and some beautiful birch trees) just outside the window, so this place really filled every corner of its expansive space with Western charm.

The next museum of the five was the Cody Firearms Museum. This museum has the largest collection of historical American firearms in the world as well as pieces from every major arms manufacturer in the world dating as far back as the 16th century! I would be lying if I said this was a museum topic that had any real personal significance to me, but the artistic, historical, and technological advancements that can be traced through the history of the firearms was fascinating even to me so I can only imagine how cool this place would be if you love guns and/or military history. Even just vicariously watching the excitement of some people’s faces as they found the guns they’re grandparents would have used during their military service was endearing in a way that you don’t really associate with guns if they’re not a part of your world. I still think they’re kind of scary myself, but I get that any object has a multitude of contexts.

As a cute nod to the Wild West Shows that helped build this museum (and the whole town around it), the museum started with a shooting gallery game. You could pick pistols or rifles, but either way I absolutely sucked. It was still a lot of fun and some impressive old-timey arcade construction.

It was cool watching the evolution of firearm design from 16th century crossbows to sleek modern sniper rifles, and the sheer size of the museum’s collection was beyond impressive. I think the museum is proudest of its beautifully well-made historical firearms like it’s large collection of fine Winchester rifles, but for me I was more interested in the oddities and failures, design trends that didn’t quite stand the test of tine. There were deeply uncomfortable looking early flintlock rifles that looked like they should be held like swords, there were air rifles with weird little pods attached to them, and there were even tommy gun style pistols! I get that as new technologies evolve it’s not always clear what’s going to work best or catch on, but you’ve gotta feel like for some of these the creators were just out of their gourd.

The guns I got the biggest kick out of seeing were the teeny-tiny revolvers and the conversely massive gatling guns. I think for me its a combo of how silly they look with how clever (and deadly) the designs actually were for their intended purposes.

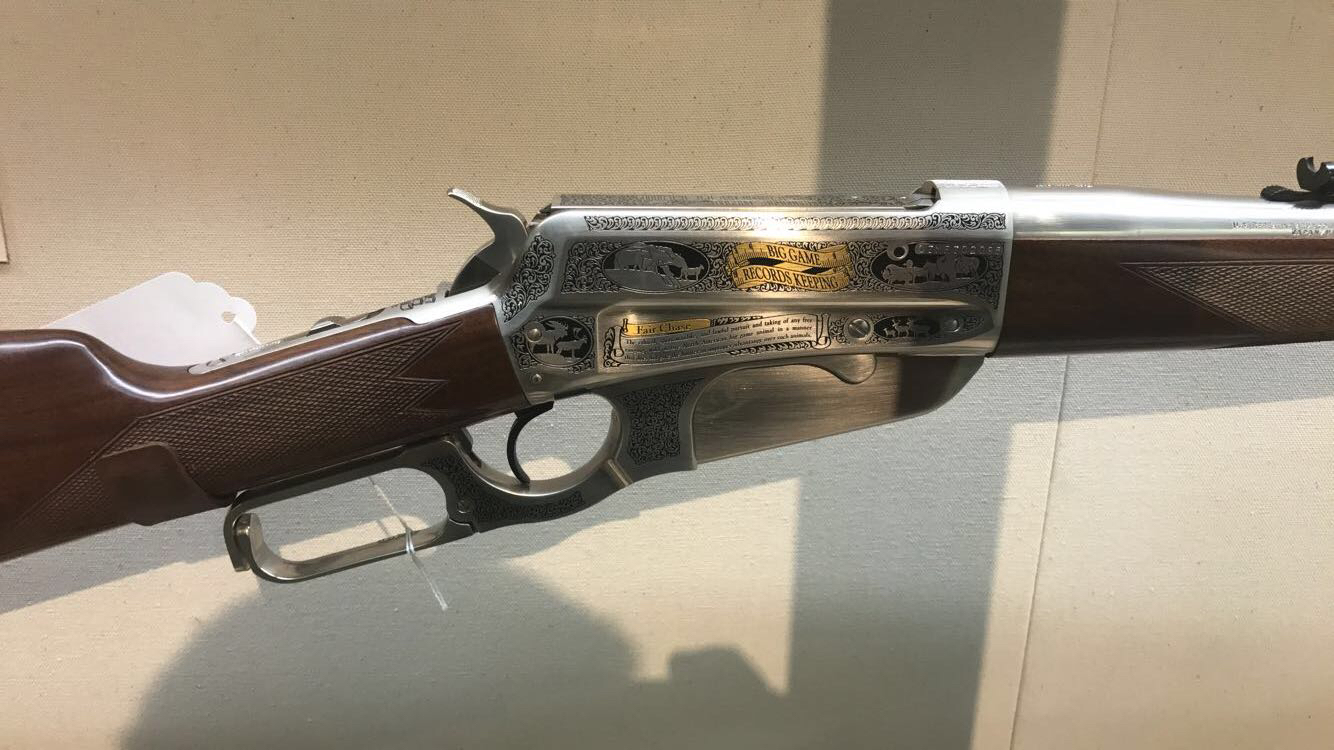

My favorite part of this whole museum though was seeing the absolutely insane and astounding artistic achievements that certain firearms makers accomplished. Whole scenes are engraved or inlaid in precious metals along the barrels, and wood and ivory handles are transformed into stylish sculptures. I never thought guns could be this pretty, but if you don’t look at this series of photos and say wow at least once I’ll eat my hat.

Other highlights included guns owned by famous figures, including one of Buffalo Bill’s biggest stars, Annie Oakley, as well as several presidents with Teddy Roosevelt unsurprisingly having the most ornate hunting rifle and Reagan weirdly having the most dainty.

Sprinkled throughout the museum was also some fine art concerned with guns and hunting with the magnificently carved wooden grandfather clock (housed in a mock hunting cabin) really stealing the show.

As I was leaving the Firearm museum, I discovered that I had somehow missed a whole floor of modern and contemporary art at the Whitney (have I mentioned this place is very big yet?) so I quickly rectified that. The pieces were in a vast variety of different styles, but something that I think really ties them together is the sublime use of color with big reds, yellows, and blues that are so characteristic of the Western landscape.

My favorites here were for whatever reason all pieces that had very unique representations of horses. They were: George Gogas’ surreal M.C. Escher-esque painting with the equally ridiculous name Judith Basin Encounter: When Charlie and Pablo had a Bad Day on the Freeway; Anne Coe’s pop-y At The End of Her Rope featuring a cowgirl wrangling a pink cadillac with creative framing used to make it seem like she’s jumping right off the canvas; Larry Pirnie’s hazy trippy Evening Run; and Steven Shrepferman’s sweetly simple earthenware sculpture Mother’s Touch.

After all those beautiful artistic representations of wildlife and landscapes, it was time to get a touch of the real thing, so the next of the five museums I went to was the Draper Natural History Museum. The hallway into this museum was filled with some stunning geological samples that give some beautiful snapshots of prehistoric Wyoming.

There was also a jaw dropping actual snapshot by Larry Burton of a field in front of the Tetons that is so goddang vibrant that it’s shocking to believe that it’s not staged or doctored in anyway.

The special exhibit in this museum was an astounding collection of rare photographic prints called Albertypes, made using gelatin coated glass plates, taken an 1871 geological survey by the photographer William Henry Jackson. Even in black and white, these photos capture such rich and detailed views of the pristine park. It’s really a special thing that they’ve been preserved for so long in such fantastic condition.

My favorites were any of the ones where you could see the artist or a surveyor hiking, because they just look so small surrounded by such grand and glorious nature.

The main attraction of the Draper though was an unbelievable centerpiece in the form of a 90 ft. rotunda with a spiral walkway through life-size dioramas of all of Wyoming’s ecosystems: alpine, mountain forest, mountain meadow, and the plains. Alongside you every step of the way were all the furry, feathered, and amphibious friends those ecosystems contain. The curation was just spectacular and the dioramas extended far overhead as well as underground (in the case of some burrowing hornets and prairie dogs) so it made for a totally immersive experience.

My favorite pieces were this stuffed moose who looks like he’s saying “I’m not crying there’s just something in my eye” and a giant bronze sculpture of buffalo falling from a cliff that is equal parts tragic and kind of amazing.

There was also lots of information about conservation efforts in Yellowstone and beyond, and the importance of caring for our natural world. One vintage forrest fire warning from the 80s really stuck out to me though for its sheer commitment to being terrifying:

After the natural history museum, I made my way to the Buffalo Bill museum which traces the life of William Cody, while also using his biography as an entry point for the larger topic of the myths and truth of the wild west. I’ll be honest, my impression of Bill before this visit was that he was pretty much just a racist huckster who represented some of the worst aspects of American opportunism, but like most things about the Old West, while there’s a kernel of truth to that description, the reality of Bill Cody was a lot more complex. As if to prompt visitors to leave their assumptions at the door, the museum greets you with a lifesize photo of William Cody when he was just 16, years away from becoming a figure of legend or even being able to grow his trademark facial hair. In that photo, he’s just a kid, and it forces visitors to see him in a different more human light.

The museum begins with a collection of artifacts, clothes, and personal belongings from the early days of Bill’s life. Right away his life didn’t begin as I would have guessed, as he grew up in a staunchly abolitionist household in the Kansas territory, and his father was so out-spoken against slavery that an angry mob attacked and stabbed him. He survived the initial stabbing, but died a few months later due to complications from his injuries. His father’s death took a toll on the family, and Bill began working as a railroad scout at the age of 11 and would go on to take all kinds of frontier odd jobs to support his family. His father’s philosophies carried over to him and as soon as he was old enough he enlisted in the Union Army (which I really wouldn’t have guessed before this) where he served as a private until 1865. He would continue to serve with the military during the Plains Wars with the Indians, but while he became Chief of Scouts he never actually achieved the rank of Colonel during battle, and it was only given to him years later as an honorary title. While as a Scout he did fight and kill Native Americans, I was surprised to learn that he would later say of that time, “Every Indian outbreak that I have ever known has resulted from broken promises and broken treaties by the government." The Indian Wars are for sure a black spot on the Government’s record, but like in every war the actions of the individuals fighting in it are largely motivated more by self-defense than ideology. Bill still didn’t have to fight like he did though, so his participation, even if skeptical, still shows him willing to sacrifice some moral beliefs for personal gain. His self-awareness about it though, does show him having relatively more progressive views on race than many of his contemporaries even if they’re not great by today’s standards. Like most Western History, it’s a bit of a mess, but I quickly realized that at the very least he wasn’t the extremely racist Indian Hunter I thought he was going in. It’s not exactly a high bar to clear, but given the time period it wasn’t a given.

One of Bill’s odd jobs, and the source of his nickname, was to hunt buffalo in order to feed the hundreds of railroad workers of the Kansas Pacific Railroad. Through a combination of strong aim and clever strategy, he was exceptionally good at this job killing a reported 4,282 buffalo in eighteen months. It seems pretty extreme giving what we know now about how close the animals came to extinction, but I guess it’s a little better that he was killing them in order to help people with inconsistent access to food survive as opposed to hunting purely for sport. The museum accompanied information about these buffalo hunts with some pretty dramatic art:

In the spirit of Buffalo Bill’s knack for using his, sometimes tenuous, connections to famous figures to enhance his own fame, the museum brought together some pieces from other American legends. These included Amelia Earhart’s flight jacket (as far as I know she had no actual connection to Bill), General Custer’s gun and uniform (Bill did briefly serve as Custer’s scout), and guns that belonged to Wild Bill Hickock, who actually was a close friend of Buffalo Bill briefly serving as an actor in his Wild West show.

The next section was dedicated Bill Cody, husband and father, areas which he didn’t really excel at. He was by all accounts a better father than a husband, really loving his kids, sending them gifts, and telling them stories when he was home, but really he was a man of the frontier and he was very rarely home with his family. He did stay married to his wife Louisa until his death, but that wasn’t really what either of them wanted. Thirty years into their marriage, they had a famously brutal divorce proceeding where she claimed that he many infidelities while traveling (likely true) and he claimed that she tried to poison him (less likely to be true, but not impossible which is crazy). Bill eventually wanted to call off the divorce because it was scandalous for the time and it was hurting the reputation of him and the show, but Louisa was rightfully pretty mad at him and wanted to see it through, only for the judge to not grant it because “incompatibility is not grounds for divorce” which is just wild. Somehow it seems like in their old age they were able to reconcile and for the last seven years of Bill’s life Louisa traveled with him and the show which is an oddly sweet ending to a pretty crazy story.

The next section was all about Buffalo Bill, legend. His rise to fame started when he was just 23 when he met a writer named Ned Buntline, who wrote a largely fictional story about his adventures for New York Weekly. The story proved popular and led to Buntline writing a successful adventure novel and several sequels about Bill. The character of Buffalo Bill took on a life of his own only tangentially related to the actual man, and the museum brought together paintings, novels, and comic books made about him from his own time through the present day which shows how surprisingly enduring he’s been in the pantheon of American tall tales.

There was even a Buffalo Bill themed board game made by Parker Bros. which in an inspired bit of Curation the museum presented with all the pieces magnified to life size proportions for extra whimsy to go with blurring of fact and fiction.

Ever the scrappy businessman, Bill decided to capitalize on all his newfound fame and he developed the idea of his Wild West stage show. Clearly Americans loved wild west stories so he decided to bring the West to them with a circus-like traveling show that combined theatrical narratives (sometimes written by his old friend Ned Buntline), feats of skill like sharpshooting and horseback riding, and sideshow elements where people could marvel at wonders and oddities from around the world. Narratively there’s not a whole lot of truth to Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, but artistically I loved the posters and the commitment to larger than life ridiculousness. Notice how much more flamboyant his showman attire is than the earlier clothes he wore when he actually was living that life for real.

Bill’s show would go on to tour the world, and he would pick up performers from all over and incorporate them into his show. This aspect of the show where Bill would bring world cultures (including those of different Native American tribes) to his audience is perhaps the messiest legacy of those shows. On the one hand the portrayals are extremely stereotyped which has aged exceptionally poorly, but while its not great it does seem more like unfortunately shrewd marketing than hatefulness on the part of Bill himself. He knew that people wanted a show that played into their exciting pre-conceived notions, but he figured that by actually hiring authentic people and performers he might still teach and expose them to ideas and people they might never otherwise see. In that way at least, he was a step above the equally popular minstrel shows of that time because at the very least when he commercialized people’s cultures he paid them for it instead of just hiring white guys to do shitty impressions. Again in this way, Bill was a bit like the West itself in that he certainly had some ugly biases, but he offered more opportunities for people of color (and women) to be paid well and live (relatively) independently in a way that most of American society didn’t. In a way, the show reminds me of the Blaxploitation films of the 60s and 70s, in that the representation wasn’t always great or progressive but it was still representation which was sadly better than most forms of entertainment offered. When Bill had money (which wasn’t always) and influence (which was usually a factor of money), he did campaign for Indian Rights and Suffrage, which does I think show that while he was often a sleazy businessman first there was a good man in there somewhere.

I was happy to see one of Bill’s most famous performers, Annie Oakley, get an entire display to herself which included some of her guns and clothes (she was so tiny for such a large personality!). Annie was one of the first breakout stars from Bill’s show eventually becoming the highest paid performer other than Cody himself. Her marksmanship was no jok, and she could shoot dimes out the air, cigarettes from her husband’s lips, and flames off of candles. She used her fame to encourage women to learn how to shoot, teaching hundreds of young ladies her self, because she saw it as an invaluable tool especially out west for defending oneself, being independent, and earning respect. Her impact on influencing a generation of women to achieve more than was previously expected of them is immeasurable.

It might sound like a hard life being part of a traveling show in the 19th century, but they had a full recreation of Buffalo Bill’s Private Tent, and I gotta admit that the man traveled in style:

In the last phase of his life, Cody as town founder, he was instrumental in establishing the town where the museum now resides. He founded ranches and hotels that brought business to the city, but he really wanted to bring in tourism to the Big Horn Basin so he set about on one of his most ambitious projects, bringing irrigation to the city. He gained the rights to divert the Shoshone river, but could not afford to build a reservoir to contain the water should it come in. He nearly bankrupted himself and his business partner, but he was able to partner with the newly created Federal Bureau of Reclamation and they built the Shoshone Dam (now the Buffalo Bill Dam) which at the time of its completion was the largest dam in the world. I saw the dam earlier in the week and was fairly impressed, but actually seeing photos from the construction and realizing what a massive undertaking it was with such limited technology its really mind-blowing that they succeeded at all.

Looking at this majestic painting of Yellowstone’s Great Falls by James Everett Stuart, you really get a sense of the boldness needed to think you can tame an elemental force like that, but credit given to Bill he did pretty much exactly that.

On the lower level of this museum, there was an exhibit all about gunfighters in the old west which, for the amount we glorify it in film and television, sounds like an absolutely nightmarish job. Still it was really cool to see vintage photographs that capture the actual humans behind the legends. Notice how not a single one of them looks particularly happy. Wild Bill Hickok (center) has a touch of smugness, but I suspect that’s mostly about still being alive that long.

They also had a small but really fun collection of famous guns and props from classic westerns, including one used by Gary Cooper, some incredible ornamental gold Colt revolvers, the guns and holsters from all the Cartwright boys on Bonanza, the Lone Ranger’s pistol, and my personal favorite the gun and signature business card of Paladin from Have Gun - Will Travel a favorite show of my father growing up that I have fond memories of watching with him.

The last little display was a celebration of the chuck wagon that supplied food for and a place to socialize for hard working cowboys. They had a beautifully restored green and white wagon, but I was even more excited to see some N.C Wyeth art depicting a wagon in action and the satisfaction on the face of a man who finally gets to eat after hours of labor.

On the way to the last of the five museums, I took a step outside to see a gorgeously green little trail with sculptures and live birds. I think I had just missed a more formal demonstration of these great Western predators of the sky, but I did see a bald eagle pretty up close which feels very fitting.

Lastly, I made my way to the Plains Indian Museum which does a really lovely job of giving the original inhabitants of the American West the credit they deserve, while also celebrating the vibrant Native culture that still exists throughout the plains. As soon as you walk inside, the museum makes a big impression with a strikingly tall teepee surrounded by sweeping black and white panoramas of untouched Western Land. The soft glow of the lights on the teepee really make it feel extra magical.

While there was a whole section of this museum dedicated to contemporary Native Art (one of the most prominent collections in the country), throughout the museum there were these incredible alabaster sculptures depicting scenes from Native legends. The sculptures themselves were fantastic but there’s something so inherently lovely and dreamy about the medium that it just elevated them into real exceptional art.

The first major displays were all of historical artifacts from different plains tribes. There were objects both ceremonial and totally mundane, but always the craftsmanship was hugely impressive. I know I say it every time, but the fine attention to detail and complex patterns that people were able do make with beads always blows my mind.

My favorite items though were the toys made for children because there’s all the same incredible craft but also a real sweetness that captures the human element at the core of the objects. I love that people even back then understood the importance of play for child development (unlike certain Puritans who might call it frivolous), and different tribes would use toys as ways to teach different skills (ranging from crafts like beading to more abstract ideas like proper social interactions) that were important for the children in a way that they might actually enjoy and internalize. Add in a photo of two contemporary Native girls playing in a field, and this part of the display was really a bit of a cuteness overload.

The next displays were about the importance of animals to the nomadic existence of many tribes. This was illustrated by a really lovely but sort of somber plaster sculpture of a family on the move. Something I learned that I never really knew about before was the importance of dogs to Plains Indian life. Before the Spanish brought horses to America, dogs were the primary beast of burden, and the Plains Indians were known as exceptional dog breeders. Dogs helped hunt, herd livestock, and even pull sleds to transport objects too heavy to carry. It’s a such a cool and rich vein of cultural history that I otherwise might not have learned about.

When horses were introduced, the Plains Indians integrated them into their lives with remarkable ease, bringing the same breeding and training skills they had learned with the dogs to domesticate and breed strong horses that made daily life so much easier. I feel like culturally for both Native and Non-Native American history, horses have such a strong tie to the imagination of the American west that it really is crazy how relatively recently they arrived here. I feel like it must have also been sort of embarrassing for the Europeans to have had horses for a long time only for some local tribes who were only just introduced them to be so much better at raising and training them. Ceremonial beaded horse head coverings and saddles also added some impressive artistic elements to the already very history.

Animals on the plains were also important for supplying raw materials to the plains Indians and I loved seeing some of the more ornate clothes made out of animals hides, from a very warm looking Buffalo horn headdress to a really beautiful and symbolically rich Elk Tooth dress to a stunning lengthy feathered headdress that had to one up the less adorned buffalo one.

Of the many uses for animal hides, my favorites were for artistic and ceremonial purposes. There were large sweeping narratives of hunts and battles played out on Buffalo hides and gorgeously died and decorated shields used in ritualistic dances that I thought were just so cool. I don’t know a lot on the subject, but to me leather seems like such a literally tough substance to work with that the light and dreamy shapes and colors that different Plains artists were able to achieve just really struck me.

The next few displays were different full scale replicas of different lodging structures. I feel like pop-culturally we sort of reduce teepees to just one type of structure, but that is pretty inaccurate as A. there were different types of teepees and B. they weren’t the only lodgings Native Americans built. Different structures served different purposes, and I particularly liked a massive domed sweat lodge that my terrible photograph really doesn’t do justice. This section had a cool light show and narrative presentation playing out over the back wall which provided interesting information and a great sense of mood, but also made this already bad photographer much worse.

Next up was the museum’s celebrated collection of modern and contemporary Native Art, which really was fantastic. While a lot of the pieces draw on traditional art in some ways, they all feel so vibrant and modern, and every artist brings their own unique flair and style to the table. I really desperately want to see more works like these break out into more museums’ modern art collections, because I never saw a lot of these artists until I went out west and that’s a real disservice to the artist, art fans who don’t have university grants to travel the country, and to Native American culture which is already pretty frequently underplayed, underrepresented, or outright misrepresented in so many museums. Even without the cultural aspect, it’s really just great art pure and simple and I wish more people could see it.

My favorite pieces included: John Isaiah Pepion’s When The Buffalo Came Back which features sleek abstracted Buffalo figures painted over Antique Ledger paper for extra symbolism; a super sweet and beautiful portrait of an elderly Native woman listening to some tunes by Louis Still Smoking; a simple but elegant gouache on paper piece called from Sea to Shining Sea by Benjamin Hajiro Jr.; a gritty dramatic battle scene by Fritz Scholder darkly entitled American Landscape; a quietly powerful reclamation of Native femininity by Holly Young painted over the music to a song called Little Sweetheart of the Prairie; a playful but striking print of David Bradley’s American Indian Gothic; and some really exceptional modern takes on traditional moccasins with a collection of different native artists making beautifully lush paintings on commercially available sneakers.

The next gallery was a classic Frontier home which shows the transition and assimilation of Native Peoples into Western society. The home showcases bright flairs of Native culture, but it is for the most part still very Westernized and what isn’t there looms almost larger than what is.

The museum ends on a more positive note though showcasing all the ways Native traditions do continue to live on in a modern context showcasing contemporary crafts, more art, and photographs from ceremonies and dances the continue to live on. The way that that Plains Indians were treated is truly reprehensible, but the resilience amidst all that pain is incredibly powerful. I wish that it didn’t have to be struggle to preserve their cultures, but I’m glad that so much does continue to live because I’m sure there were times where that was greatly uncertain. I think an important take away though is not to pat ourselves on the back as a society because the culture didn’t get exterminated, but to look at what’s here and think about just how much more was lost. I’m glad we’re making progress, but it’s a long way from done.

I don’t think the museum could have picked a more wonderful and optimistic image to end on than this sweet portrait of a young Native Woman graduating from University. Her outfit reflects her culture and her diploma and cap show off her strength and intelligence. She’s linked to the past even as she starts her future, and her big smile shows off a confidence that’s truly infectious. You don’t have any doubt that she’s going to do something great.

With five museums down, I had one hell of an appetite so I got a great big lunch from a brewpub called Pat O’Hara’s. I got an incredible Hot Beef and cheddar sandwich, which featured a mount of slow cooked prime rib sliced and liberally doused with melted cheddar and bbq sauce on a fluffy ciabatta roll. It probably clogged every artery in my body, but my god did it hit the spot. I cannot stress how consistently good all the beef has been out here, and throw in some thick salty french fries and you’ve got a pretty perfect lunch. I washed it all down with their home-made malty Irish Red, which went down easily and made you want another. I had quite a bit of driving to do though, so I resisted that particular urge.

Along the three hour drive to my Air BnB, I did have to take a brief pit stop in the wildly named town of Thermopolis to marvel at just how ruggedly amazing the scenery was:

After a long day of learning and driving, I made it to the town of Lander where my Air BnB was and decided to reward myself with some super good homemade ice cream from an amazing place (that has sadly closed now called) Ken and Betty’s. It had a super cute Mom and Pop vibe, and I have to admit their peanut butter cup fudge ripple was just heavenly. Just the perfect thing to end a long but really nice day.

Favorite Random Sightings: Mudd Coffee (the second d doesn’t make it more appetizing); Granny's Diner (such a classic americana name); Bottoms Up Lounge (If this were a gay club it would be perfect but alas I don’t think that’s the case)

Regional Observation: There are oddly confrontational road signs on the highways that say “Buckle up, buttercup” and it made me laugh every single time.

Albums Listened To: Turn the Radio Off by Reel Big Fish; Turn! Turn! Turn! by the Byrds; Tuxicity by Richard Cheese; Twelve Reasons to Die by Ghostface Killah (a weird blend of Gangsta rap and classic Italian Giallo)

People’s Favorite Jokes:

(an oldy but a goody) What do you call cheese that isn’t yours? Nacho Cheese

Songs of the Day:

from their 20th anniversary tour of the album

Between baby Crosby and the go go dancers this one’s kinda surreal

What a showman

super sleek